Trooper Linwood Greene, Jr.

Troop C 28th U.S. Horse Cavalry

A few days after mailing the letters to the troopers, Linwood Greene, Jr. called me to schedule a meeting. He said he could meet anytime. I didn’t have to give him directions to our home. He told me he knew Cincinnati like the back of his hand. In addition, he was a lifetime member of the 9th and 10th Horse Cavalry Association so he was very interested in my plans. Greene arrived at our home in his big, new Cadillac. We lived on a narrow, dead-end street so his car was noticeable in our neighborhood. This was our first meeting with a World War II Buffalo Soldier. He brought a list of names and wanted to schedule a meeting with the other troopers as soon as possible. Carmon took our picture as we discussed our plans. During the conversation, he asked why I had “that guy” on my wall. He was referring to a photograph of President Ronald Reagan shaking hands with me. I told him about my military experience in the White House. He shook his head and said that he disliked him since he didn’t do anything for black folks.

Greene smoked cigarettes and talked loud. Sometimes we would ask him to refrain from smoking but he did as he pleased. He was a strong willed man with strong convictions. When he was in the military, his nickname was Sergeant Bulldog. Here is his story.

Linwood Greene, Jr. was born on March 8, 1920 in Hubbell, Kentucky. When Greene and I talked about his birthplace he called it ‘No Name Kentucky.’ It was a small place compared to Cincinnati. His mother moved the family to Madisonville, Ohio when he was two months old. Madisonville is a section of Cincinnati. During the summers and during school breaks, he returned to the family farm. He earned 2 dollars every week working on the farm. This money was used to purchase new school clothes for the fall.

He said “We would work six days per-week and went to the Baptist church and stayed there all day on Sundays.”

Linwood Greene, Jr.

BSRM Collection

Greene attended Withrow High School and graduated in 1941. While in high school he played baseball and football. He received a scholarship to play football at Norfolk State University, a predominately black college in Norfolk, Virginia. Linwood return home to Cincinnati after 1½ years. His parents were having financial difficulties so he got a job to help his family. Money was tight due to the war; food, gasoline, shoes, and fuel oil were rationed. He worked in the foundry at the Westinghouse Corporation. He got married six months later then, received his draft notice.

We went to the induction station as Fort Thomas like all the other draftees from Cincinnati. Greene told me that many thoughts went through my head…. Will I make it back home? The war going on and people were getting killed right and left. When I arrived at the in-processing station on March 3, 1943 it was cold. We were placed in an all-black section of the processing facility. The group I was with was notified that we were going to the cavalry. Most of the young men with me had never ridden a horse. They were city people. I learned to ride horses on the farm as a teenager. We were assigned seats on a military troop train. Someone said we were going to Texas and someone said we were going to California. The train stopped in Indianapolis to pick up more recruits. It seemed to me that there were more recruits from Cincinnati and Indiana than any other place. It took three days to get to Camp Lockett, California. Like other troopers assigned to the 28th Cavalry, after basic training, he was assigned to the Machine Gun Troop. During basic training, we learned how to ride and shoot at the same time. We took good care of our horses seven days a week. There were about 200 horses in our troop but when there was a post-wide pass-in-review ceremony, there were nearly 3,000 horses.

When they left Camp Lockett in 1944 to go overseas, his unit was split-up. He was assigned to the all-black 92nd Division and joined the combat engineers as a welder. Although some of Greene’s stories are sketchy, he frequently shared this one with us. Six days after arriving in Europe, he was wounded when riding in a jeep that ran over a mine. His commander was killed and he would pull up his shirt to show us a scar across his chest. He told us that he also has shrapnel in his head, hand, and stomach and that he received a Purple Heart medal for his bravery.

Trooper Greene like the other men from the Cincinnati returned home after the war. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 better known as the GI Bill. President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill into law on June 21, 1944. It provided education and training and backed loans to purchase a home, farm, or business. Funds could also be used for unemployment pay of $20 a week up for to 52 weeks and job finding assistance. A top priority was to build Veteran Administration hospitals and review military discharges.

The suburb was born. The shopping centers followed. Roads had to be built to connect communities. The engine of economic growth churned. Dreams came true. Men and women of all backgrounds who served honorably in the U.S. armed forces made something of themselves. Their accomplishments raised expectations for their children and for future generations. And the G.I. Bill worked. Returning veterans were given first priority when applying for federal jobs with the U.S. Postal Service and the railroad.

The Buffalo Soldiers returned from Europe and took advantage of the GI Bill. Trooper Linwood Greene, Jr. retired from the railroad with over 30 years of service. He was a member of the ‘Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels.’ During our interview with Trooper Garrett from Somerset, Kentucky he said he was also member.

The Honorable Order of the Kentucky Colonels began with the first Governor of Kentucky, Isaac Shelby, in 1812 that bestowed on his son-in-law, Charles S. Todd, the title of Colonel. Governor Shelby later issued commissions to all who enlisted in his regiment in the war of 1812. Later Governors commissioned Colonels to act as their protective guard. They wore uniforms and were present at most official functions.

From

that day to the present, each incumbent Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky,

upon assuming office, becomes the Commander-in-Chief of the Honorable Order

of Kentucky Colonels and issues all Commissions at the discretion of his

office to recommended and deserving recipients. This tradition has grown

into the most unique honor any state can bestow. Any individual so honored

by the Governor is eligible for membership in the Honorable Order of Kentucky

Colonels.

There are no membership dues but all Colonels are encouraged to contribute

to the charitable fund of the Honorable Order known as “Good Works

Program” which has developed into one of Kentucky’s most significant

charitable efforts. The order has its annual Banquet held at the Galt House

in Louisville each Kentucky Derby Eve and some outstanding celebrity are

featured as the entertainer.

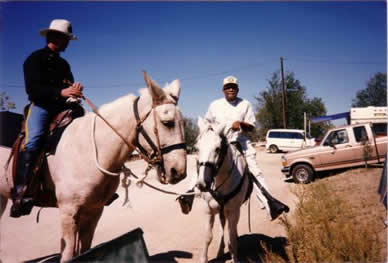

Linwood Greene, Jr. in white cap, 1991

BSRM Collection

Trooper Greene was proud of his membership in the Shriners/Masons. His duties would take his around the United States. He was responsible for organizing the mounted horses in parades. His love of horses started as a child and well into his 80’s he still enjoyed riding.

Greene’s son, PFC Paul H. Greene was killed in Vietnam. He was 19 years old. Greene told us that Paul came home on October 15, 1965 and said that he wouldn’t see them again. In February 1966, he was killed. Paul’s name is on the Vietnam Memorial in Washington DC. Greene always believed that serving in the military was a positive experience for him although there were heartaches and sadness. He did regret not finishing his education at Norfolk State University.

In 1991, Greene and his wife, Metholyn, returned to Camp Lockett for the reunion of old soldiers. His photograph and interview were featured in the San Diego newspaper. He told reporters, “It’s hard to believe, but this is where it all happened.”

Greene was active in all of the Heartland Chapter events. In 1999, we sponsored an exhibit booth at the Indiana Black Expo in Indianapolis. He and the other troopers interacted with the crowd all day and into the evening. Greene didn’t stop there; in the evening, he was invited to parties to socialize and pass out his business cards. He told us that we needed to hang with him. Trooper Linwood Greene, Jr. died in 2003.